In

“Technology, Finance and Dependency: Latin American Radical Political

Economy in Retrospect,” Matias Vernengo takes another look at dependency

theory especially as it pertains to the development of Latin America

since the development of the theory. In particular, he looks at how to

reconcile the fact that several periphery countries have in fact been

able to industrialize despite dependency theory. For Vernengo, the

dependency has transferred from the trading of goods to a more financial

peonage, one where debt is the controller of the nation’s destinies at

the periphery.

I

think having a look at Dependency theory is important because for me so

much of economics is both relational and a process. I think it is too

easy to look at a developing country and say to yourself, “Oh that is so

sad, we must do something!” This idea springs forth from the idea that

nations exist in a vacuum and not as part of some world-system. Vernengo

looks at both the Marxist and the Structural traditions of dependency

theory and sees that their commonality lies in the agreement that “the

core of the dependency relation between the center and the periphery

lies in the inability of the periphery to develop an autonomous and

dynamic process of technological innovation” (552). Vernengo argues that

the focus on the technological is wrong as it is finalization that has

trapped the developing nations in their peripheral role. In my view of

the argument, I am more sympathetic to Vernengo’s argument. In the

course of my lifetime I have seen dollar flows come in and crash Mexico

and Russia and South East Asia and Argentina etc. This is not to

discount Baran or Prebish or the schools they worked in. Capital has

many tentacles.

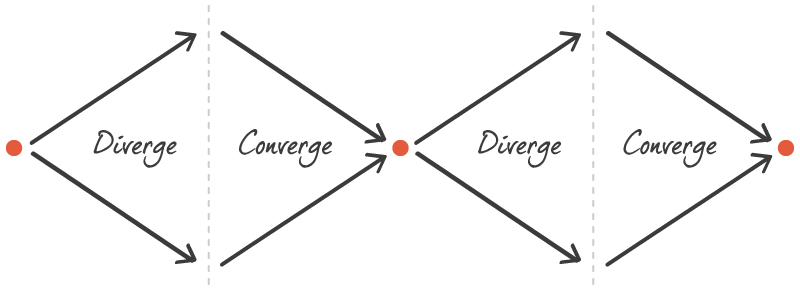

What

thinking about dependency theory has done for me is to make me think of

the totality of the system so that we are not looking at individual

nations in isolation. What this does is make me somewhat pessimistic

about the possibility of growth. I was thinking specifically of some

mathematical truisms. For example, if a country has an initial GDP per

capita of 50 units, and they can grow their output in one year by four

percent, at the end of the year, they will now have an output of 52

units. If this can be sustained year over year, we would laud this

nation for growth over and above what rich nations would do, even if we

would point out that a higher level of growth would be expected from

developing nations because they are not at the technological frontier.

The problem with looking at one nation in isolation is that if you look

at a comparative nation that is twice the size of the first nation. The

second nation has an initial GDP per capita at PPP of 100. This second

nation only must grow at a two percent rate to equal the absolute gain

of the first nation. If the growth rate of the country twice the size

maintains the growth that is half of the smaller country, the gap

between the countries will never close. At some point there will have

been enough growth that the fifty-unit gap will be trivial, but we all

know what the master said about the long run.

I

was interested in taking this thought away from the thought experiment

and into the real world. What I did was to go to the World Bank Website,

and I pulled their data for GDPs per capita for purchasing power

parity. Aware of the limitations of GDP per capita in not catching the

distribution of output internally, it was still a good first pass for

what I was interested in seeing, as its standardized output per person. I

then took the GDPs and expressed them as a ratio of the least developed

country in 2017, here the Central African Republic. The CAR GDP per

capita in 2017 was just under 726 dollars at purchasing power parity.

What is enough to make a person pessimistic is to see just how high the

ratios go. My pessimism driven though experiment was too optimistic.

There are 45 statistical divisions with a ratio higher than 50. The

implication here is that mathematically is that if any of these nations

with a higher GDDP per capita than the Czech Republic grows two percent,

then the Central African Republic needs to literally double its economy

over a year to keep up.

This

is mathematical truism makes me wonder about the possibility of

convergence, as even China, which has been lauded as a growth miracle

over the past thirty years, only has a ratio of 23, meaning that in

comparison to the richest countries, per person it is only a quarter of

the size. So much of its growth in absolute terms has been the sheer

number of people China has. So if we look at that as our best case, if

we really want to talk about the possibilities for convergence, we would

need to be thinking about much slower growth or even-degrowth in the

core countries, and I have a feeling that politically that is a very

heavy lift because the core countries do not want people looking at

development in terms of a world system, but would prefer that people

look at the poor countries and ignore that there is a structural cause

and that there is an ahistorical reason that the people of Niger are in

need.

Works Cited

Vernengo, Matias. “Technology, Finance, and Dependency: Latin American Radical Political Economy in Retrospect”. Review of Radical Political Economics, Volume 38, №4, Fall 2006, 551–568

Work Bank. GDP per capita, PPP (current international $). (n.d.). Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ny.gdp.pcap.pp.cd

| GDP Per Capita Ratio 2017 | |

| Country Name | Ratio |

| Central African Republic | 1.00 |

| Burundi | 1.01 |

| Congo, Dem. Rep. | 1.22 |

| Niger | 1.40 |

| Malawi | 1.66 |

| Mozambique | 1.72 |

| Liberia | 1.77 |

| Sierra Leone | 2.10 |

| Madagascar | 2.14 |

| Togo | 2.29 |

| Gambia, The | 2.34 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 2.34 |

| Haiti | 2.50 |

| Burkina Faso | 2.57 |

| Uganda | 2.57 |

| Ethiopia | 2.62 |

| Chad | 2.67 |

| Afghanistan | 2.72 |

| Rwanda | 2.81 |

| Low income | 2.97 |

| Kiribati | 3.00 |

| Mali | 3.05 |

| Guinea | 3.09 |

| Benin | 3.13 |

| Heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC) | 3.30 |

| Solomon Islands | 3.34 |

| Zimbabwe | 3.35 |

| Yemen, Rep. | 3.58 |

| Nepal | 3.71 |

| Comoros | 3.78 |

| Least developed countries: UN classification | 3.84 |

| Lesotho | 4.03 |

| Tanzania | 4.06 |

| IDA only | 4.15 |

| Tajikistan | 4.40 |

| Vanuatu | 4.42 |

| Kenya | 4.53 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 4.62 |

| Senegal | 4.75 |

| Micronesia, Fed. Sts. | 5.09 |

| Cameroon | 5.12 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 5.13 |

| IDA total | 5.24 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding high income) | 5.27 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 5.28 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa (IDA & IBRD countries) | 5.28 |

| Pre-demographic dividend | 5.29 |

| Bangladesh | 5.33 |

| Tuvalu | 5.41 |

| Cote d'Ivoire | 5.42 |

| Mauritania | 5.44 |

| Cambodia | 5.52 |

| Zambia | 5.54 |

| Papua New Guinea | 5.78 |

| Marshall Islands | 5.84 |

| Fragile and conflict affected situations | 6.13 |

| Ghana | 6.19 |

| West Bank and Gaza | 6.73 |

| Sudan | 6.75 |

| Honduras | 6.87 |

| IDA blend | 7.41 |

| Congo, Rep. | 7.50 |

| Pakistan | 7.61 |

| Moldova | 7.85 |

| Nicaragua | 8.05 |

| Nigeria | 8.09 |

| Pacific island small states | 8.19 |

| Tonga | 8.21 |

| Myanmar | 8.49 |

| South Asia | 8.95 |

| South Asia (IDA & IBRD) | 8.95 |

| Samoa | 9.13 |

| Angola | 9.15 |

| Vietnam | 9.33 |

| Uzbekistan | 9.46 |

| Cabo Verde | 9.50 |

| Lao PDR | 9.67 |

| India | 9.72 |

| Lower middle income | 9.91 |

| Timor-Leste | 9.94 |

| Bolivia | 10.41 |

| El Salvador | 11.03 |

| Guatemala | 11.23 |

| Guyana | 11.24 |

| Morocco | 11.32 |

| Philippines | 11.49 |

| Belize | 11.72 |

| Eswatini | 11.90 |

| Ukraine | 11.94 |

| Jamaica | 12.46 |

| Jordan | 12.61 |

| Bhutan | 12.91 |

| Fiji | 13.16 |

| Armenia | 13.29 |

| Early-demographic dividend | 13.34 |

| Dominica | 13.80 |

| Namibia | 14.39 |

| Georgia | 14.72 |

| Kosovo | 14.79 |

| Low & middle income | 15.08 |

| IDA & IBRD total | 15.45 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 15.96 |

| Ecuador | 15.96 |

| St. Vincent and the Grenadines | 16.18 |

| Tunisia | 16.41 |

| Middle income | 16.69 |

| Indonesia | 16.92 |

| Sri Lanka | 17.68 |

| Mongolia | 17.80 |

| Albania | 17.83 |

| Paraguay | 18.02 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 18.06 |

| Peru | 18.51 |

| South Africa | 18.59 |

| Middle East & North Africa (excluding high income) | 18.71 |

| Middle East & North Africa (IDA & IBRD countries) | 18.86 |

| IBRD only | 18.94 |

| St. Lucia | 19.23 |

| Nauru | 19.50 |

| Colombia | 19.94 |

| Lebanon | 19.95 |

| Latin America & Caribbean (excluding high income) | 20.39 |

| Palau | 20.42 |

| East Asia & Pacific (excluding high income) | 20.53 |

| East Asia & Pacific (IDA & IBRD countries) | 20.75 |

| Grenada | 20.83 |

| Suriname | 20.88 |

| Algeria | 21.02 |

| Macedonia, FYR | 21.06 |

| Serbia | 21.25 |

| Brazil | 21.33 |

| Latin America & the Caribbean (IDA & IBRD countries) | 21.65 |

| Caribbean small states | 21.73 |

| Latin America & Caribbean | 21.77 |

| Dominican Republic | 22.08 |

| Maldives | 22.94 |

| China | 23.15 |

| Iraq | 23.28 |

| World | 23.35 |

| Arab World | 23.36 |

| Botswana | 23.40 |

| Costa Rica | 23.52 |

| Azerbaijan | 23.97 |

| Upper middle income | 24.50 |

| Late-demographic dividend | 24.51 |

| Thailand | 24.62 |

| Turkmenistan | 24.79 |

| Gabon | 24.90 |

| East Asia & Pacific | 24.99 |

| Mexico | 25.17 |

| Barbados | 25.51 |

| Belarus | 25.95 |

| Montenegro | 26.66 |

| Libya | 27.04 |

| Middle East & North Africa | 27.42 |

| Europe & Central Asia (excluding high income) | 28.33 |

| Argentina | 28.63 |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 28.71 |

| Bulgaria | 28.86 |

| Europe & Central Asia (IDA & IBRD countries) | 29.38 |

| Mauritius | 30.73 |

| Uruguay | 31.08 |

| Small states | 31.42 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 32.33 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 33.59 |

| Panama | 33.71 |

| Chile | 33.94 |

| Russian Federation | 35.17 |

| Other small states | 35.56 |

| Croatia | 36.21 |

| Kazakhstan | 36.41 |

| Turkey | 36.53 |

| Romania | 36.72 |

| Greece | 38.02 |

| Hungary | 38.72 |

| Latvia | 38.84 |

| St. Kitts and Nevis | 39.36 |

| Central Europe and the Baltics | 39.94 |

| Poland | 40.12 |

| Seychelles | 40.31 |

| Malaysia | 40.57 |

| Bahamas, The | 41.92 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 43.50 |

| Slovak Republic | 43.55 |

| Portugal | 43.63 |

| Estonia | 43.73 |

| Europe & Central Asia | 44.99 |

| Lithuania | 45.45 |

| Cyprus | 47.53 |

| Slovenia | 48.03 |

| Czech Republic | 50.04 |

| Spain | 52.34 |

| Israel | 52.71 |

| Korea, Rep. | 52.81 |

| Puerto Rico | 53.54 |

| Aruba | 54.29 |

| Italy | 54.31 |

| Malta | 56.53 |

| New Zealand | 56.63 |

| European Union | 56.74 |

| Oman | 57.41 |

| France | 59.03 |

| United Kingdom | 59.60 |

| Japan | 59.62 |

| OECD members | 59.73 |

| Euro area | 60.13 |

| Finland | 61.80 |

| Post-demographic dividend | 63.91 |

| Canada | 64.34 |

| High income | 65.17 |

| Bahrain | 65.47 |

| Belgium | 65.90 |

| Australia | 66.75 |

| Sweden | 69.16 |

| Germany | 69.76 |

| Denmark | 70.75 |

| Austria | 72.18 |

| Netherlands | 72.32 |

| Iceland | 73.22 |

| Saudi Arabia | 74.08 |

| Cayman Islands | 80.14 |

| North America | 80.22 |

| United States | 82.01 |

| Norway | 84.60 |

| Hong Kong SAR, China | 84.77 |

| San Marino | 87.35 |

| Switzerland | 89.14 |

| Kuwait | 99.10 |

| United Arab Emirates | 101.77 |

| Ireland | 104.21 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 108.60 |

| Singapore | 129.36 |

| Luxembourg | 142.91 |

| Macao SAR, China | 158.58 |

| Qatar | 176.84 |